#otd1945.06.23

“Where are our parents? You Nazi murderers …”

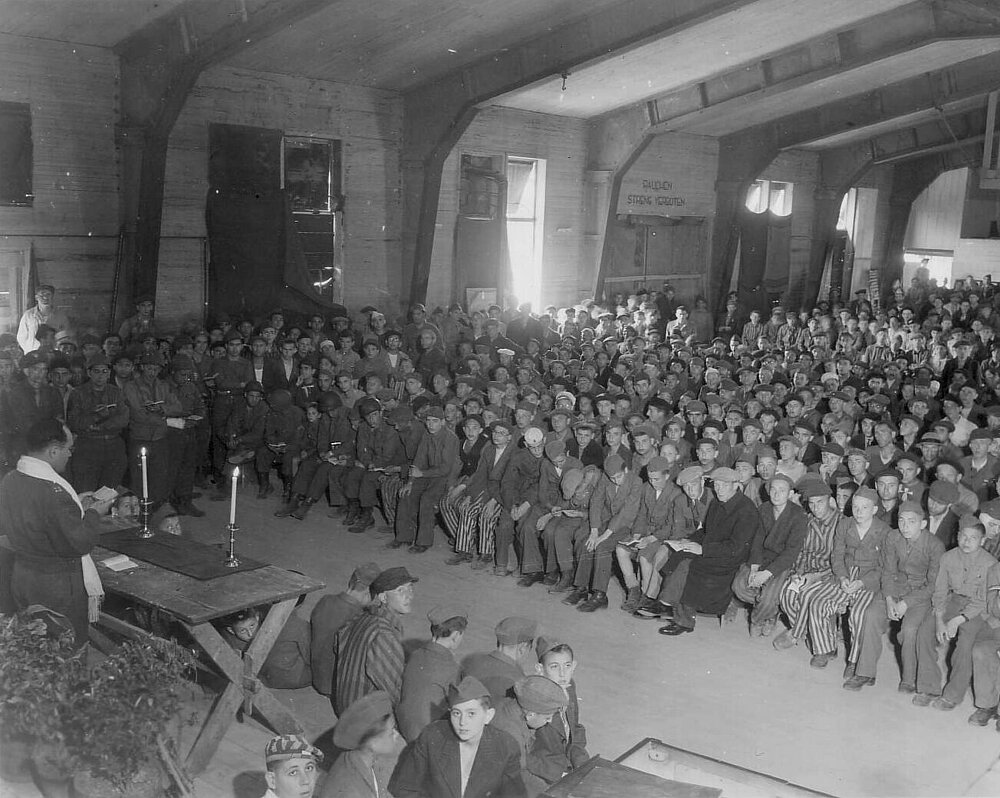

On 23 June 1945, 350 children and adolescents from Buchenwald arrived in Switzerland. Accompanying them was Rabbi Herschel Schacter, a U.S. Army chaplain who attended to the liberated Jews in Buchenwald. What were the circumstances leading to their journey?

On 22 April 1945, 11 days after the liberation of the Buchenwald concentration camp, the Jewish Aid Committee had issued an appeal to the public: “Rescue the rest of Central Europe’s Jewish youth!” The same day, Herschel Schacter had sent a request for help to the office of the Œuvre de secours aux enfants (OSE) in Geneva. The Paris-based Jewish children’s aid agency responded immediately, and Jewish organizations in Switzerland, France, and the U.S. began looking for means of accommodating the young people. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the Red Cross joined in the effort.

Photo: Charles W. Herr (National Archives at College Park, Maryland)

The majority of the 904 minors among the Buchenwald survivors in mid-April 1945 were over 15 years of age. The few younger children owed their lives to the solidarity of political inmates. Janek Szlajfstajn and Stefan Jerzy Zweig, for example, – the very youngest at 4 years old – had been hidden in the inmates’ infirmary and the Little Camp; Soviet inmates had concealed 11-year-old Menek Schiller in Block 30; his 13-year-old brother had survived along with other children under the protection of Jewish inmates in Block 23; 6-year-old Isaak Goldblum had been in “Children’s Block 66” in the Little Camp; and 7-year-old Israel Lau in “Children’s Block 8”.

Photo: George A. Haynia (National Archives at College Park, Maryland)

Most of the Jewish children and adolescents in Buchenwald had been left orphaned and homeless. The Schiller brothers found their mother in the former Meuselwitz subcamp. A few returned to their native countries with their compatriots from the camp. The 17-year-old Leopold Huppert, for instance, travelled to Prague in May 1945 with the liberated Czechs. He and other adolescents from Terezín, Dachau, and Buchenwald were admitted to Štiřín Castle. The building housed one of the convalescent homes the pedagogue Přemysl Pitter had established in vacant castles for orphaned Jewish children.

Photo: James E. Myers (National Archives at College Park, Maryland)

The first passenger train carrying Jewish children and adolescents left Weimar station on 5 June 1945. It took 427 young people – boys from Buchenwald and girls from Bergen-Belsen – to the French town of Écouis, where they were warmly received. There they were to recuperate, make contact to relatives, and decide where to go next. In addition to France and Switzerland, the United Kingdom also took in hundreds of Jewish youth in the summer of 1945.

(Willy Fogel; Buchenwald Memorial)

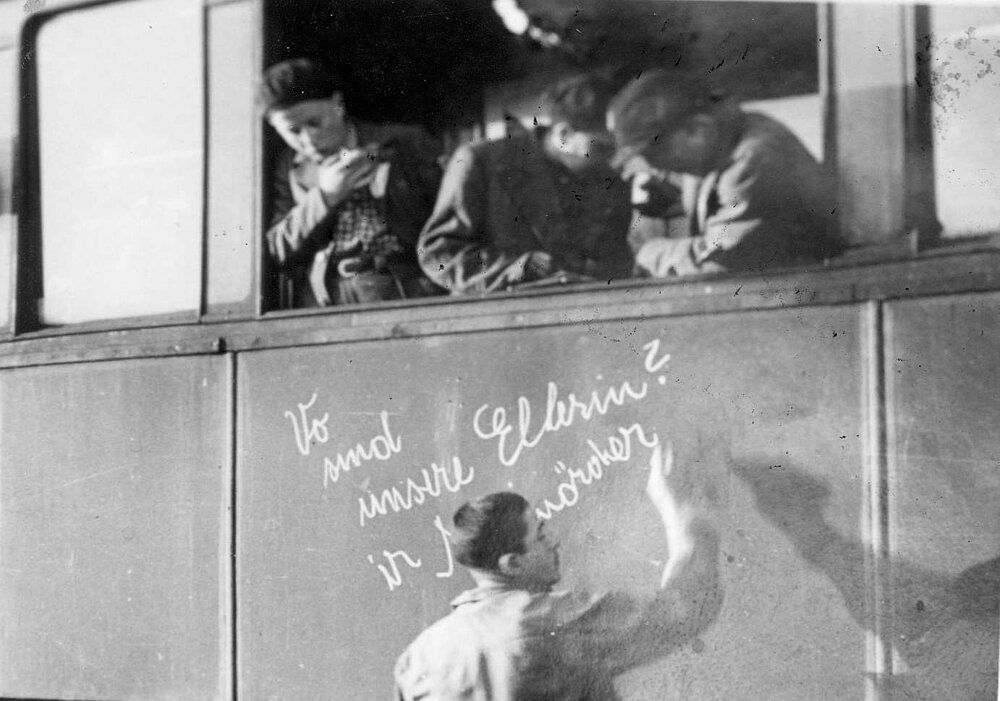

On one of the trains to France, the 15-year-old Josek Dziubak, who had survived in Block 66, wrote the words “Vo sind unsere Elterin? ir Nazimörder…” (“Where are our parents? You Nazi murderers …”). It took him two years to find relatives in the U.S. to take him in. Many years later, another one of that group, Robert Wajcman, recalled: “Joe really spoke for us all. We had all just begun to comprehend how few of our family members were still alive.”

(Harry Stein)

References:

Judith Hemmendinger, Die Kinder von Buchenwald, Rastatt 1987.

Ronald Hirte and Fritz von Klinggräff, Israel, fragen nach / Europa: Gespräche über einen fernen, nahen Kontinent, Weimar 2020.

Pavel Kohn, Schlösser der Hoffnung: Die geretteten Kinder des Přemysl Pitter erinnern sich, Munich 2001.

Madelaine Lerf, “Buchenwaldkinder” – eine Schweizer Hilfsaktion: Humanitäres Engagement, politisches Kalkül und individuelle Erfahrung, Zurich 2010.